So far all of Willa’s overnighters were women and girls who traveled hours to get to their appointments in Sioux Falls. The came from tiny towns like Colome, Veblen, and Dupree, places that Willa knew only as dots on a map. Or they came from cities large enough to have small airports and hospitals and shopping malls like Mobridge or Aberdeen. Willa gave them a bed to sleep in while the state’s twenty-four-hour legal waiting period passed.

Conroy Glashoff was the ob/gyn who flew in from Minneapolis each week. Without him, there wouldn’t be anywhere in South Dakota to get an abortion. “We like to move him around to avoid threats,” the staffer from Planned Parenthood told Willa over the phone. “Are you sure?” “Sure I’m sure,” Willa said. She signed up to have him stay with her for his fly-ins in December, one night each week of the month. “It’ll be nice to have a man in the house,” she added after their goodbyes, but the staffer had already hung up and her words frittered away.

Willa had read an interview of Conroy Glashoff during her training. “Women want this procedure,” he’d been quoted as saying, “and if I have this capability, I will provide it. Because many will not.” She admired his willingness to do what not a single doctor in the state would do. Yet he compared himself to a gravedigger, regarded as one of society’s bottom feeders. “Abortion was specifically forbidden by the original text of the Hippocratic Oath,” he pointed out. His words stayed in her memory, and she felt a slight hum of excitement at the prospect of meeting him in the flesh.

On the first Wednesday she expected him, Willa put fresh sheets in the spare bedroom and clean towels in the guest bathroom. She’d spruced up these rooms when she’d begun volunteering for the overnights a year ago. She’d painted the walls a warm white, bought new green sheets and yellow towels, and installed a flat screen television in the bedroom so her guests could watch programs in private if they wanted. On the bathroom vanity she assembled a basket containing sample-size soaps, shampoos, and lotions just like in a hotel. A can of shaving cream and a disposable men’s razor were added for the doctor’s visit, and the floral soaps and fruity shampoos were replaced with a piney brand Rex had been fond of. Conroy Glashoff would be the first man to sleep in the house since Rex had died two years ago.

Men and the company of men. That was something Willa missed. And sex. That too. She was learning to do without. Married at twenty, she had been a wife for thirty-six years. Rex was the only man she’d ever slept with, and a part of her thought he would also be the last. Now, at the age of fifty-eight, she didn’t think she had it in her to reveal herself to another man. She’d inspected herself in the privacy of her bathroom and couldn’t imagine exposing her limp breasts, the white hair between her legs, or the rough skin rimming her buttocks to strange eyes, strange hands. She was convinced Rex had recalled her fresher, younger self whenever he looked at and caressed her naked body, as if that former lovely self were still radiating within the person she’d become.

When she opened the door for him, Willa saw Conroy would have no use for the shaving supplies she’d put in the bathroom. He had a trim gray beard and moustache and spiky silver hair. She’d heard he was sixty-five, but he seemed younger. He was exactly her height with clear skin and a boxy physique. Underneath his coat, he wore jeans and a black cashmere v-neck sweater over a white t-shirt. ‘Hip,’ that’s what Willa’s daughter Sandra would call him. Or maybe ‘arty.’ He studied her with his light brown eyes in a way that suggested recognition. She felt herself flush and then straightened her posture as they shook hands and introduced themselves. His hand was warm and firm.

“Mind if I smoke?” Conroy asked after she’d shown him the spare bedroom with the pale green bedding.

“Not in the house,” Willa said. Some of the women and girls she’d hosted had been smokers. She’d fixed up a little smoking area on the deck with a lawn chair and an ashtray and a view of the fields, stretches of flat that were grassy prairie in summer and blankets of snow in winter.

“I’m surprised you smoke,” Willa said as he bundled up to go outside. “A doctor. I thought you’d know better.”

“Well,” he said, grinning, “I’m surprised by your hair.”

Willa laughed and touched her hair. She had stopped dyeing it auburn and the growing-out gray gave her the wild look of a skunk. She forgot how odd it was until she caught a glimpse of herself in the mirror. If she didn’t mention it herself, no one brought it up, and she thought she might just as well be invisible.

“As for the smoking,” Conroy said, “it’s do as I say and not as I do.” He leaned his head in close toward her face. His top teeth were straight and even, but his bottom teeth were crowded and didn’t line up perfectly. His breath was cool and clean, as if he’d just eaten a mint.

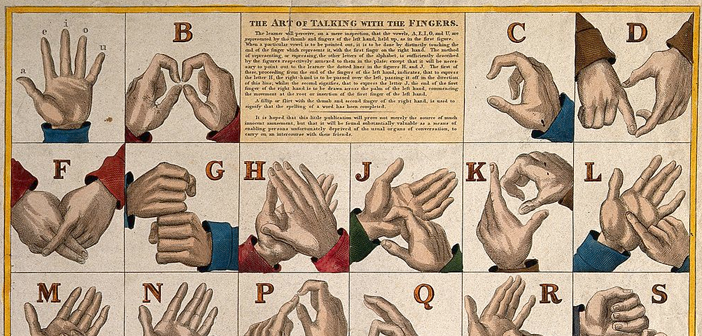

Willa took a step back from him, startled by how close his face had come to hers. In her nervousness she found herself raising her arms and signing what he’d said, repeating his words out loud as she moved her hands and fingers in patterns through the air. Runaway hands. That’s what Rex had called this tic of hers.

Conroy raised his eyebrows. “How about that.”

“I teach the deaf,” Willa said. “I used to.” She shrugged. “Reflex.”

He clasped her hand with his warmer hand. “Do it again.” She repeated her gestures, this time without talking. He squinted at her. “How do you say ‘reflex’?”

She signed the word. She hoped he would touch her hand again, but he didn’t.

He went out to the deck with his cigarettes, and she dimmed the interior lights and followed the speck of red that was the cherry of his ash as he raised it to his mouth and tapped it in the ashtray. Then she brightened the lights and went to stir the clam chowder warming on the stove.

She’d gotten into the habit of making a pot of soup for her overnighters, serving it with a green salad and a baguette from the bakery downtown. Some ate a lot, others hardly took a bite. Soup seemed like something even the ones with the poorest appetites could manage to get down.

She’d already eaten herself, but she offered Conroy the chowder and sat at the table across from him. He asked for tabasco and shook the spicy liquid into the soup. He ate the first bowl quickly and requested a second. With the bread he sopped the soup bowl clean and soaked up the dressing from his salad plate.

Before the women and girls arrived, Willa gathered the framed baby and childhood photos of Sandra and put them in a closet, along with the ceramic handprint she’d made Willa in kindergarten that said Number One Mommy and hung from a brass nail in the kitchen. There was no reason to hide any of this from Conroy. He noticed the pictures and asked about Sandra, who worked in Chicago as an editor for a textbook publisher. “My daughter is an actor,” he said, with a pride that disarmed Willa and made her smile. Most people she knew in Sioux Falls would think acting an indulgent pursuit–no way to earn a living. “A stage actor,” Conroy said, in the same confident, assured way a South Dakotan might say judge or accountant, doctor or CEO.

As they chatted Willa noted the absence of a wedding band. It might not be practical for a doctor to wear one. Some married men never did, although Rex always had. Willa had taken her rings off a year after Rex’s death. Signing at first felt different without the rings, but she’d gotten used to it.

Conroy didn’t mention a wife, and Willa didn’t mention Rex either. She found she didn’t want to; it was nice not to wear the mantle of a widow for the night.

There was something curious about the conversation besides the fact that spouses hadn’t come up. It wasn’t the words they were saying to one another. They were ordinary words. Would Willa share her chowder recipe? Was snow forecast for the night? General small talk, nothing of import. It was something apart from the words, a feeling that seemed to be emanating from Conroy to her. It felt as if he were touching her internally, inside her chest, putting light fingerprints on the surface of what she could only call her heart. To be sure of it, she almost wanted to ask, “Is it just me? Or does it feel like I’m touching you too–on the inside?” A vibe, that’s what Sandra said she got when she met a man she liked. Willa called it chemistry.

Conroy went out to smoke again while Willa did the dishes. She hurried the task, wishing she had something to serve for dessert, or that she’d already offered to put on a pot of coffee. He might go directly to his room once he was done with his cigarette. When he came inside he pulled out a chair and sat back down at the kitchen table, and Willa felt a swell of happiness. She finished wiping the counter and took the seat across from him, not bothering to rinse and wring the rag, depositing the wet lump of it in the sink.

“A teacher,” he said. “Tell me more about that.”

“I used to teach here in town,” she said. “At the school for the deaf.” With cochlear implants and mainstreaming into regular schools, she told him, there were hardly enough students to keep the residential school open. Soon the state would shut it down for good. Willa had been given an early retirement six months ago. Now she taught American Sign Language at the community college, mostly to kids who thought it would be an easy way to satisfy their foreign language requirement.

“It’s not the same,” Willa said. “I miss it.”

“What do you miss?”

“I miss the awe.” She regretted her words the instant she’d said them. They were too serious, too heavy and ponderous to share with someone she’d just met.

Conroy’s eyes stayed on hers, his pupils large and black. The expression on his face was inquisitive, not skeptical. He rubbed his silver beard with his hand, and she felt she could safely tell him more.

“I was in awe of my students,” she said. “Especially because I’m a hearer.” She pressed her fingertips to her temples and looked down, thinking of how to explain it. When she looked up, his eyes were still on her.

“When Sandra was little I used to drop her off at elementary school on my way to work,” she said. “Then I’d drive to my job. First the one school, then the other. Do you know when hearing kids and deaf kids sound the same?”

Conroy shook his head slowly.

“Recess.” Willa smiled. “Playground noise. But when recess is over it’s two different worlds again. The signers and the speakers. I felt awe to pass from one realm to the other.” Willa tilted her head. “Does that make sense?”

“Yes.” He leaned toward her, putting his elbows on the table. “I feel it sometimes too. It can happen with the late terms. Once I delivered a woman at twenty-four weeks. I’d just done a termination for a woman with the same gestational dates as the one who’d given birth.” He held his hands out, palms up. “There’s this baby in the NICU only a few hours after the other procedure.”

“I don’t think I could do it,” Willa said.

“You have to believe in what you’re doing.” He glanced at his watch. “Time to turn in?”

“It probably is,” she said. She wished he hadn’t brought the conversation to an end. She wished he wanted to stay talking with her as much as she wanted to keep talking to him. But he was right; he had to be at the clinic early for appointments.

He bent over to tie his shoe before he got up from the table and Willa watched. His shoe was black, soft leather with a rounded toe; his socks were argyle, black with blue and green diamonds. The watch on his wrist was gold with a white face; silver hairs curled over the brown crocodile band.

There was a neatness and precision about him. You could tell he was careful about his clothes, his person. It was very appealing, his way of being. At Sandra’s urging, she’d gone to some Rotary Club luncheons in the last few months and had met several men who’d been friendly, but they were men with the large bellies or scrawny frames of aging who’d only made her long for Rex and the husky boyishness he’d always possessed.

After Willa settled into bed, the phone rang. She was still wide-awake. She picked up the phone and said hello. A woman asked for Rebecca, and before Willa could reply wrong number, the woman whispered, “Murderer.” Willa hung up. The phone rang again. This time it was a male voice chanting a prayer: “Let us pray for the salvation of the killers of babies and wounders of women.”

Conroy knocked softly on Willa’s bedroom door. She opened the door in her nightgown, the phone in her hand.

He was wearing a blue plaid flannel shirt and gray sweatpants, his feet in white socks. The shirt was halfway unbuttoned revealing a mat of silver hair on his chest.

“I heard the phone,” he said. “Cranks?”

Willa nodded.

“Maybe it’s best to take it off the hook,” he said.

Willa clicked the receiver on, heard the buzz of the dial tone, and shoved the phone under the pillow shams she’d piled on the chair next to her bed.

“How do they know?” Willa asked.

“They know,” he said. “I’m sorry it’s happening to you.”

Willa went to her bed and got under the covers. Conroy stayed in the doorway. She clicked off the lamp on her bedside table. “I’m okay,” she said. She rolled over, turning her back to him. She wasn’t scared. A little unsettled, a little angry, but not scared. From what she’d observed of the extreme pro-lifers in Sioux Falls, they were all bluster and swagger, consumed with theatrics. Like children throwing tantrums. Best not to pay too much attention. She had a hard time mustering the alarm the clinic staff seemed to expect of her with their warnings and protocols.

She waited for him to shut the door and block out the rectangle of light shining in from the hallway, to leave and return to his room on the other side of the house. She watched the red-lighted minutes change on her clock. Then the hall light went out, the door closed, the room darkened. She heard Conroy’s footsteps creaking across the floor, not walking down the hall toward the guest room, but coming closer to her in the bed. The mattress dipped and shifted as he settled his weight, lying down on top of the covers on the right side of the bed, the side that had always been Rex’s.

“What are you doing?” Willa said softly, sitting up and turning to look at him in the faint glow of her nightlight. The inside of her chest felt warm and fluid.

“I don’t know,” he said. “Should I go?”

Willa closed her eyes and shook her head. She breathed in deeply, smelling his odor of cigarettes, toothpaste, and the fresh, evergreen smell of the soap she had put in the basket, the one Rex had liked. She hadn’t imagined the feeling. There was something between them. Or he wouldn’t have done this unexpected thing. And now it felt even stronger, like a shared pulse. She didn’t dare touch him or she might start shaking. It was enough to have him right there next to her. This was proof of something. A bold gesture; a risk taken for her. She was glad he’d done what he’d done. It didn’t leave any room for doubt. She took the duvet that was the topmost cover of her bedding and folded it over him. Then she burrowed deeper into her remaining blankets. She wrapped her arms around herself and squeezed tightly. She hoped he wouldn’t be cold in the night.

“I don’t know if I’ll be able to sleep with you here,” she said to him after a few minutes. “I might not be able to.”

“Shhhh,” Conroy said. “You will.”

*

Willa decided to make lentil soup for Conroy’s second visit. She set about chopping onions, carrots, and celery as soon as she finished her morning coffee, sautéing the diced vegetables in a few tablespoons of oil.

When she’d awakened after his first overnight, he was no longer in the bed beside her and the shower was running in the guest bathroom. The duvet she’d covered him with had been folded back over her. The pillows and blankets on the right side of the bed were crumpled with the imprint of his head and body. At breakfast they made no mention of their shared night. The only reference to the harassing phone calls came from Conroy. He gave her a sheet of paper with three phone numbers on it–work, cell, and home–and told her to call if there was any trouble. There hadn’t been. In the last week, Willa had put up her Christmas tree, strung it with lights and hung it with ornaments. Nothing eventful.

She noticed she’d begun to mark time by how long it would be until Conroy’s next visit. She checked the five-day weather forecast to see whether his flight might be delayed or grounded due to a snowstorm. She was elated to see a string of bright yellow suns for all the days to come.

He popped into her head in bits and pieces, sudden images of the crooked line of his lower teeth, the glistening bristles of his beard, his hands tying the laces of his shoe, tugging up his argyle sock. The evergreen fragrance of her Christmas tree reminded her of the soap and shampoo he’d used from the basket in the bathroom. When she slipped under her duvet at night, she imagined him cocooned within it beside her.

After she finished preparing the soup, Willa sat to read the newspaper in the sunshine of her kitchen and found herself struck by an urge of surprising intensity. A warm pressure between her legs pulled her away from the articles, and she gave into it, folding shut the paper and closing her eyes. She crossed her legs and squeezed her thigh muscles, coaxing the tingle into something more, until she knew it wouldn’t fade. It made her laugh to feel so aroused in the middle of the morning, dashing up to her bedroom and drawing the curtains, foregoing the pillow between her legs and using her hands instead, unhooking her bra to touch her nipples. This wasn’t the rote purging she’d become accustomed to since Rex had died. She was astonished to feel her body respond like this again, to hear the sounds coming from her mouth. She still had her sap–that’s what Rex had always said about her in the bedroom. But this was because of Conroy.

An hour before he was due to arrive, Willa took the lentil soup out of the fridge and started it simmering in its silver pot on the stove. She turned on her porch lights and the bulbs of her Christmas tree and then went outside to see how the lighted tree looked from the street. On her front step, there was a package. She held it in her arms as she walked to the mailbox at the end of her drive to take in the view of the tree. This holiday she’d used all white lights, a departure from the colored lights Rex had insisted upon, and she liked the pristine effect. Back in the house she ran the blade of a scissors through the band of clear tape sealing the box flaps.

She dug into white styrofoam peanuts and pulled out an amorphous shape wrapped in red tissue paper. She peeled off the outer layers, smoothing out the sheets of tissue and folding them into squares. Six items were within the larger bundle. She tore the red paper off one of the smallest, a light cylindrical object, and uncovered the plastic leg of a baby doll. Shiny red drips had been painted on the end of the leg that snapped into the doll’s hip socket. The other tissue-wrapped shapes were the remaining parts of a dismembered baby doll, the head, torso, two arms and another leg, all painted with the same red drips. A black envelope of photos was taped inside the box. The color pictures showed severed fetal parts laid out on a metal tray–recognizable arms and legs, and close-ups of hands and feet with tiny nails. Nothing Willa hadn’t seen before. Yet it was still bewildering to think of someone going to so much trouble to spook her; they’d be disappointed to see she wasn’t more undone. Glorified pranksters is what she thought.

Rex had once been mailed a box of human feces when he’d supported a Sioux candidate for a seat on the city council. “Mailing a package of crap is surely proof of shit for brains,” he typed in a letter to the editor of The Argus Leader. “If you can’t speak with words, you must not have anything to say.” The Sioux contender lost the election, and Rex’s letter wasn’t printed in the paper, but Willa still had a carbon copy of it in a keepsake box in the attic.

She showed the baby doll and photos to Conroy when he arrived. As he stood next to her, she felt tenderness for him, and pleasure to be in his company, hearing his voice, smelling his aroma of mint and tobacco. His smile made her think he was glad to see her too. She had the sensation of being touched on the inside again, of something invisible connecting them.

“I honestly thought it was a Christmas gift,” Willa said. “They’d have my hide at the clinic for being so cavalier.”

“I won’t tell,” Conroy said. “Was it mailed or delivered?”

“Mailed,” Willa said, flipping the box to show the Sioux Falls postmark.

“That’s good,” Conroy said. “Nobody was here.” He picked up the box to take it outside and put in the trunk of his rental car. “I’ll get rid of it tomorrow. At the clinic. Maybe I’ll give it to the protesters.” He smiled. “Regifting.”

“I like your tree,” he told her when he came back from the car. Then he raised right hand and swooped it in a circle in front of his face, signing Beautiful.

Willa signed back, Thank you.

Conroy shook his head. “I only know that one word. That’s as far as Google got me.”

Willa had postponed her own dinner and they ate the lentil soup together. Tonight she had used cloth napkins and put out red-glass votives. At the last minute she left the candles unlit, not wanting to appear too suggestive of romance. When she’d set the table, she had remembered the bottle of tabasco. Conroy shook it into his soup. “Your hair is coming along,” he said, tearing off a slice of bread from the baguette, his fingers dusting white from the floury crust.

Willa smoothed her hair with one hand. She wore it in a chin-length bob and the gray hair had grown so that there was just a narrow band of auburn around the bottom edge. “To tell you the truth,” she said, “I kind of like it like this.”

“Why?”

“It’s not the usual thing,” she said. “It’s freeing. To do what’s not expected of me.” She tucked her hair behind her left ear, wincing as her finger grazed the lobe.

“What’s wrong with your ear?” Conroy said.

“It’s nothing,” Willa said. That morning she’d noticed the skin around the gold stud had become red and puffy.

“It looks infected.”

“It comes and goes.” She shook her head. “It’s no big deal.” She scooped her hair from behind her ear to cover it up. Conroy stroked his beard and raised his eyebrows.

“Funny story,” Willa said. “I got them pierced for the first time with one of the girls who stayed with me earlier this year. On a whim.” But it wasn’t a funny story. She didn’t know why she’d said that it was. It was a sad story, and Willa decided not to share it with Conroy. She got up from the table to clear the dishes. She shooed him out of the kitchen, refusing his offers to help, telling him to go outside for his after-dinner smoke while she got the kitchen in order.

The girl’s name was Regina. She was nineteen, a tall, thin ethereal girl with long, straight blonde hair. Her cool slenderness made Willa think of nothing so much as an icicle. She already had a six-month-old baby when she’d come for her appointment in January. Willa had bought a Pack n’ Play portable crib and put it in the guestroom. She agreed to sit for the baby while Regina was at the clinic.

The baby Lark was one of the most pitiful babies Willa had laid eyes on. Unsmiling and skinny, her nose crusted and gooey with snot, she was so pale and bald you could see blue veins through the skin of her skull. Regina lived with her mother in Edgemont. No husband. No job.

Regina hadn’t brought enough diapers and Willa had had to go out and buy more. At dinner, she refused soup and salad, eating only bread and butter, scraping the soft yellow cream off the top of the stick lengthwise. The way she moved her hands was fluid and graceful–a natural for signing. There was a poise to her gestures, and her posture and carriage too, that made Willa want to recast her as a ballerina.

While she nibbled at her bread, picking bits of white out of the crust and popping them into her mouth, she told Willa her plans if she won the state lottery’s Mega Millions. “First off, I’m going to have a big party. A supper. At the Victory Steakhouse in Edgemont. Or maybe in a rented hall, catered. Right before we start to eat I’m going to tell everyone there how much they mean to me. With a microphone. I’ve got all the words memorized in my head.” Regina’s eyes became wet as she spoke. “Then after my speech I’ll say, look under your plates. And you know what they’ll find? A big check. A big check from me to them.” Willa listened with Lark propped between her arms fussily sucking on a bottle of formula. She wanted to ask Regina about school, but didn’t for fear of giving offense.

In the morning, Regina came to breakfast white-faced and agitated, the tie for her pink velour robe undone and trailing. Lark was still upstairs asleep in the Pack n’ Play. Stirring oatmeal at the stove, Willa watched Regina dip her spoon into the sugar bowl and slip a large spoonful of white crystals into her mouth, her movements shaky, not elegant and sure as they’d been yesterday. When Willa sat at the table with her oatmeal, Regina said she’d changed her mind. She wanted to cancel her appointment. Lark had cried off and on all through the night, and Willa wondered if Regina wasn’t thinking straight from lack of sleep.

“I can’t kill my unborn baby,” Regina said.

“If that’s how you feel,” Willa said. “If you’re certain.” Willa felt an ache of sadness for Regina, and Lark, and the mother back in Edgemont. She didn’t feel anything for the unborn baby that had swayed Regina.

Regina calmed down once the call had been made to the clinic but still seemed dispirited. “I have to follow my heart,” she said in a hollow voice. “I couldn’t live with myself if I didn’t.”

They had nothing to fill the hours once the appointment was cancelled. “Let’s make a day of it,” Willa said, hoping to cheer up Regina. “What would you like to do? My treat.” Regina decided she wanted to get Lark’s ears pierced, so everyone would know she was a baby girl, and get a third piercing for her own ears. “Could we go to Empire Mall?” she asked. “That’s where I got my ears pierced the last time I was in Sioux Falls.”

All three of them got piercings, including Willa, who’d been ribbed by Sandra for years about her ‘virgin’ earlobes. They ate lunch at the Royal Fork Buffett where Regina loaded a plate at the dessert bar with cakes, cookies, pie, and puddings. The next morning, Willa put Regina and Lark back on the bus to Edgemont. Last month Regina had sent Willa a picture of Lark, her earrings still huge on her small translucent ears, and also the new baby, a boy she’d named Wentworth after a movie star she admired. Willa sent Regina a VISA gift card for one hundred dollars and a Mega Millions lottery ticket.

When Conroy came back inside from his smoke, Willa asked if he wanted to watch a video of a play performed in American Sign Language. She had ordered the DVD of a production of Twelfth Night that she used to show to her students every December. They sat together in the family room and watched it with the captions on so Conroy could follow along, the darkened room lit by the t.v. and the white glow of the Christmas tree. He seemed to genuinely enjoy it, and laughed in all the right spots. Not everyone could handle the silence of it, but Conroy spread his arms across the back of the couch and propped his feet on the ottoman, seeming perfectly at ease. His fingers touched Willa’s shoulders a few times, and they exchanged smiles.

“I thought you could take it home to show your daughter,” Willa said when it was over. “The stage actor. And your wife.”

“I will,” he said. “Thank you. They’ll like it.”

That night when Willa was settled in bed, she wondered how long it would take her to fall asleep. He was married. Now she knew for sure. She imagined his wife in bed in their home, missing Conroy, maybe touching herself and thinking about him just as Willa had that morning. When was the last time Conroy had made love to his wife? Last night? Early this morning? She wished she hadn’t mentioned his wife after all. You couldn’t know how a marriage worked from the outside.

She heard Conroy’s footsteps approaching. He knocked gently on her bedroom door. She swallowed quickly and breathed in.

“It’s open,” Willa said. The door swung into the room, the light from the hall making its rectangle on the floor.

He was there in his flannel shirt and sweats. “Want some company?”

Willa sat up in bed and stared at him. Okay, she signed.

“That’s yes?” He touched his beard with his hand, a shy, questioning look on his face.

Willa nodded.

He lay down beside her on top of the covers. She lifted the duvet off of herself and folded it over him on the right side of the bed.

A part of her wanted to touch him, and wondered why he didn’t reach for her. Maybe he thought she’d run and hide. Another part of her thought their resisting in nearness was tantalizing, and she wanted to make it last as long as she could.

“Good night, Willa.”

“Good night, Conroy.”

*

“What’s the soup of the week?” Conroy asked when he arrived for his third visit, unwinding a scarf from around his neck in Willa’s foyer. It was snowing and she brushed the flakes from his shoulders, watching one that had come to rest on his silver eyebrow melt away. He had a small mole in his eyebrow that she hadn’t noticed before, and she added it to what she’d stored up.

“Minestrone,” Willa said.

“How are your ears?”

Willa lifted her hair and showed him. They were the same as before. Irritated, sometimes there was pus. “I’ll have to look into it I guess.”

He unzipped a pocket of his suitcase and pulled out a little white cardboard box, and a tube of cream. “Here,” he said. “These might help.” In the box on top of a sheet of cotton, attached to a square of black, velvety cardboard, was a pair of earrings–small, elegant knots of gold. “They’re nickel-free,” he said. “You might be allergic. I hope you like them.” His eyes met hers. “I thought they looked like you.” The tube contained an antibiotic cream: erythromycin. “Use it once a day,” Conroy said.

It made her feel courted to know she’d been on his mind during his week away in Minneapolis, that he’d gone to the trouble of getting the earrings and cream for her. In her delight she hardly knew what expression to put on her face. “This is such a surprise,” Willa said. “Thank you. You shouldn’t have.”

“I wanted to.”

Willa applied the cream to her ears and put on the new earrings before they sat down for soup. She lifted her hair to model the earrings for him. “Nice,” he said. He signed Beautiful, and she laughed.

“Still no haircut?”

“Nope.” Willa touched the auburn fringe that bordered her bob, pulling a strand toward her face to eye the dark ends. “I’ll look like a regular person again when I do.”

“You could always dye it and start all over again.”

“Maybe I will.”

Willa lit the three red-glass votives in the center of the table and they sat to eat the minestrone.

Conroy added tabasco to his soup and brought up the next week, which would be his last overnight with Willa. “I was thinking,” he said, his voice tentative, “that instead of just the one night, I could take an extra day off work and stay two nights. We could go and see Falls Park the second night, not worry about turning in early. I hear the park’s all lit up for Christmas. Not to be missed. We could skip the soup, and go out to dinner. What do you say?”

“That could work,” Willa said. She fixed her gaze on his, hoping he could read from her eyes how much she wanted to spend those two nights with him.

He smacked his palm softly against the table and smiled. “Great. Great,” he said. “So it’s a plan.”

Her eyes shifted to his mouth, traveling along the imperfect line of his lower teeth, imagining running her finger or tongue along them. What would he tell his wife? How would he explain the extra day in Sioux Falls with Willa? Maybe he wouldn’t mention her at all. Why did it matter what he said? It was between the two of them. She was outside it.

This time when Conroy went out to smoke, Willa left the dishes and put on her coat and gloves and hat and joined him. The snow had stopped and the fresh fall was soft and sparkling and immaculate in the darkness, its whiteness giving off a cool luminescence. “Watch,” she said, and inserted an orange extension cord into the outdoor outlet. The deck became rimmed in warm white dots of light from the strings of bulbs Willa had twined along the railing. “You,” Conroy said, turning to her, but not saying anything else. Willa caught his eye and they looked at each other until it felt as if his eyes were getting too far inside her and she had to look away. She wanted to go close to him and hold his face with her gloved hands, and to touch his lips. She wondered what it was like to kiss a man with a beard, and felt flustered thinking of all the other things she had imagined about him when he was gone, scolding herself for indulging in fantasies. She wished she weren’t thinking about a man who belonged to someone else.

“Unplug the lights when you come in,” she said, hurrying inside to get to the dishes.

That night after Willa changed into her nightgown, she left the door to her bedroom open. Soon she heard Conroy come down the hall. He entered her room, closed the door, and lay down on the bed beside her on top of the covers, as he’d done twice before. She switched off the lamp and folded the duvet over him. They lay together in the dark.

“I was wondering,” Willa said, trying to make her voice sound casual. “Why do you do it?”

“I thought you knew why,” he said. “I like you, Willa.” She made a soft appreciative noise.

“No. Your job. Flying here every week.”

“My job? I saw what it was like when it was illegal. At the end of my residency. Younger doctors don’t know. Bicycle spokes, knitting needles, Lysol. Perforations, raging infections. I had to give a seventeen year old a hysterectomy once. I have plenty of reasons beyond those, but that’s enough for starters.” He rolled over to face Willa. “Your turn.”

This was why Willa had started the conversation in the first place: so he would be prompted to ask her “Why?” in return.

“I had one,” she said. “It was when Sandra was five. She was in kindergarten, and I was teaching full-time again. I didn’t want another baby. It was legal. I went to my doctor in town and he took care of it. No questions asked. No waiting period.” And here was the part Willa had most wanted to share. “I didn’t tell my husband. He would have tried to change my mind. I kept it from him. I lied.”

“Sometimes you have to,” Conroy said, “to get what you want.” He reached over and touched her chin and turned her face toward him and they looked at each other in the darkness, but for once Willa didn’t feel connected to him. She’d hated keeping that part of herself sealed off from Rex when he’d known every other thing about her. She didn’t think he would have forgiven her for not telling him. But she was also sure he would have wanted her to have their second child. “I need another little Sandra,” he’d said as their daughter grew, wistful for another pregnancy in spite of Willa’s refusal.

“We should go to sleep,” Willa said, and turned away, staring at the red numbers on her clock.

Conroy was the only one Willa had told apart from the Planned Parenthood staff when they’d interviewed her. What was her experience with abortion? they’d wanted to know. The fact that she’d deceived her husband about her abortion had had a big impact on them; it seemed to earn their trust.

The year before he died Rex had thanked her on their wedding anniversary. “What for?” she’d asked.

“For never making me wonder. For never having gone astray.”

“What a thing to say,” Willa said, though they’d known their fair share of couples whose marriages had been broken by unfaithfulness over the years.

“I’m lucky,” Rex said. “That’s all.”

She could have told him then that she’d gone astray, though not in the way he’d considered, but she didn’t. And she hadn’t told Sandra when Sandra had had her own abortion five years ago. “Too bad my life can’t be like yours and Dad’s,” Sandra had said tearfully when the man backed out of taking her to her appointment.

It took Willa a long time to fall asleep. She listened to Conroy’s steady breathing for nearly an hour before she drifted off.

At 1:22 in the morning the doorbell rang, waking them both. “I’ll go see,” Conroy said. He walked down the hall to the guest room and she heard snapping, zipping, and the crunching tear of velcro as he put on his kevlar vest. Willa followed him downstairs in her robe. She flicked on the outdoor lights. The soft, fresh snow in Willa’s front yard was dotted with two-dozen small white crosses. “Fantastic,” Conroy said. “Terrific. Spirit of the season.”

“Should we call the police?”

“For this? No. Don’t give them the pleasure. I’ll take care of it.” He dressed and gathered the crosses, throwing them in the trunk of his rental car. When he came back inside, his nose was red from the cold and Willa cupped her hand over it.

“You’re chilled,” Willa said. “You need to warm up. You should get under the covers.” Returning upstairs, she turned back the layers of bedding on the side where Conroy slept while he changed back into his flannel shirt and sweats. He rejoined her in her bedroom and both of them got under the duvet, blankets, and sheets. His hand, still cool, moved beneath the linens to the curve of her hip. She rested her warmer hand on top of his, and he gave her a small squeeze. Cat and mouse, Willa thought, that was the game they were playing with one another.

*

On the Monday before Conroy’s last visit, among the batch of Christmas cards in her mail, Willa received an envelope she couldn’t place. She was suspicious at first, after the package two weeks ago. There was a return address on the envelope, but no name. It was from Edgemont, South Dakota. The only person Willa knew from Edgemont was Regina, but the handwriting didn’t match the swollen, childish cursive of Regina’s prior letter.

Inside the envelope was a card with a picture of two fluffy white kittens drinking milk from a blue bowl. A newspaper cutting from the Edgemont paper slipped out from the fold of the card. Willa saw a black-and-white photo of Regina. It was her obituary. She’d died right after Thanksgiving, at the age of twenty. It didn’t say the cause of death. “Died at home.” That was it. She was survived by her daughter Lark, age sixteen months, and her son, Wentworth, age three months, and also her mother. Willa hadn’t known Regina had graduated from high school and been a majorette marching in front of the band in parades. She should have asked her about school after all. She pictured Regina in a sequined leotard, prancing in white boots, twirling a silver baton and tossing it in the air, catching it behind her back. It suited her. Willa titled her head back and pressed her fingers to the corners of her eyes. She opened her mouth and exhaled.

She read what Regina’s mother had written:

It got to be too much for her with the two of them. The boy had colic.

The state is setting them up for adoption. They’re so little they say they’ll be taken right away. They’ll probably be kept together as sister and brother. I don’t think the names will stay the same. Regina liked those names, so that’s too bad.

I hope it’s not a cloud on your holidays. I thought you’d want to know. Regina said you were kind to her when she was in Sioux Falls.

I found her in the garage, on the rafters. Everybody wonders, nobody asks. She didn’t leave a note.

God bless you and thank you for helping my daughter Regina, may she rest in peace, with the Lord’s love to you and yours now and forever.

A hanging. It was hard to imagine such a gentle and delicate girl doing such a thing. It was too violent and brutal. Regina had been determined.

Would a note from Regina have made a difference to her mother? Willa didn’t know. She recalled Regina’s girlish voice saying, “I have to follow my heart. I couldn’t live with myself if I didn’t.” Her voice had had a peculiar absence to it; it had sounded the way Willa’s had in the days following Rex’s death.

At the funeral home, Willa had put a note in the breast pocket of the navy suit Rex was buried in. “I’m sorry, Rex. I wish I hadn’t had to keep it from you. I didn’t know how else. It was the right thing for me.” She signed the note, “Your devoted and loving wife, Willa.” Did such an after-the-fact confession count for anything? What, she wondered, was the good of a letter that couldn’t be answered?

*

The day before his last visit, Willa called Conroy. She dialed the home number written on the sheet of paper he’d left with her on his first overnight. His wife answered. Good. That was what she’d hoped for. No chance that the sound of his voice might make her waver. And no chance that she’d reconsider after speaking to his wife.

“Who?” the wife said, and Willa explained who she was.

“Oh,” the wife said. “I can’t keep track.”

“I’m sorry to say I have to cancel his last stay with me this week,” Willa said. “I’ve been getting some calls. Death threats. I’m not comfortable. I’ll let the people at Planned Parenthood know.”

There hadn’t been any death threats, and even if there had, Willa thought Conroy would know by now she wouldn’t have been deterred by them.

The wife understood. She said she would tell him. “Tell him I’m sorry,” Willa said. “Be sure to tell him how sorry I am.” The wife said she would.

Rex had always said cheating was the easy thing to do. “Just do whatever feels good, damn the consequences.” Now Willa felt certain Rex had never been tempted. Or he’d have known he was wrong. He’d have known how hard it could be to take that leap, to grab the thing that was there for the taking. Just as hard as staying true. Maybe harder. Regina couldn’t bring herself to take what Conroy offered; Willa couldn’t either. You wanted to, but something held you back. Something failed you.

Willa’s ear hurt from the phone pressing against it. She went to her bathroom and when she saw herself in the mirror, she took the scissors out of the medicine cabinet. They were old scissors that she’d used to cut Sandra’s hair and give her bang trims when she was a girl. There was a faint coating of orange rust on one of the blades. For a while she’d used the scissors to snip away the white hairs between her legs, until there had been too many to keep up with. Willa took the scissors and cut off the last of her auburn hair, catching the soft trimmings in her palm. She dropped the hair in the toilet, and flushed, but the auburn threads dispersed and floated on top of the water. The hair was too light and wouldn’t sink, instead just swirling on the surface. She unrolled a length of toilet paper and massed it on top of the floating hair, and that gave it weight and helped make it go down.

She went back to the mirror and removed the gold knots from her earlobes and put them in a drawer of the bathroom vanity. They were nice earrings. Maybe she could send the earrings to Regina’s mother for her to give to Lark. She dabbed alcohol on her inflamed earlobes with a white ball of cotton. She wondered how long it would take for the holes to seal up, and whether they would leave a mark. She stared at her reflection, at her gray hair and bare ears. She clenched her hands. I wanted you. That was what she wanted to sign. She could picture the motions, the formations of her fingers. But she didn’t move. Her hands stayed at her sides.

This piece was originally published in Midwestern Gothic and has been reprinted here with permission of the author.

Ann Ryles was a finalist for the 2013 Flannery O’Connor Award for Short Fiction and a semifinalist for the 2014 Iowa Short Fiction Award. She is a graduate of the MFA in Writing Program at the University of San Francisco and UC Berkeley’s Boalt Hall School of Law. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in The Minnesota Review, Your Impossible Voice, Gargoyle, Pear Noir!, Konundrum Engine Literary Review, and Stirring: A Literary Collection. She lives in Moraga, California with her husband and their two daughters.

Ann Ryles was a finalist for the 2013 Flannery O’Connor Award for Short Fiction and a semifinalist for the 2014 Iowa Short Fiction Award. She is a graduate of the MFA in Writing Program at the University of San Francisco and UC Berkeley’s Boalt Hall School of Law. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in The Minnesota Review, Your Impossible Voice, Gargoyle, Pear Noir!, Konundrum Engine Literary Review, and Stirring: A Literary Collection. She lives in Moraga, California with her husband and their two daughters.