Az Got volt gelebt oif der erd, volt men im alleh fenster oisgeshlogen.

If God lived on earth, all his windows would be broken.

The old man stands at the bedside, hands cupped, steam braiding up from the bowl like ascending phantoms. Rails of light peel through the window slats, score tense wires of gold on the walls. She is writhing beneath the duvet, clutching her pillow, screaming . . . a high terrible wail, mournful, undulating . . . like the struggle of train brakes.

“Take some soup,” he says. He dips his spoon, offers it to her lips, but she swipes it away, sends it clattering to the tiles.

It was the same scream in Stryj, metallic, rhythmic, with the dirty water pouring out of her and the doctor refusing to look him in the eyes. For two nights she screamed, her skin shedding heat, while he pressed cold towels to her head, and for two nights the fever did not break and the baby would not come, and the doctor could not once look him in the eyes. On the morning of the third day he left her to go visit a friend, a druggist on Kilinskiego Street who sold bloodsuckers.

Hat cocked low, his coat frayed at the bottom, he tramped through the market square. The weight of the evil eyes like a clinching pressure around the yellow band on his arm. At the corner, he felt the solid bite of a nightstick on his woodsman’s shoulders, but he did not flinch, did not break pace.

When the druggist ignored the bell he banged hard on the glass and cried out so that anyone might hear, “Sabka is dying!” Out of fear or pity, the old Pole cracked the door open and passed him out a cup. He took it, threw a gold coin onto the steps.

At the hospital the nurse spread the beasts over her face and plump arms, and dripped water over the heads until they fell off, blind and polluted. It was a miracle, certainly it was a miracle that both mother and child survived. And the boy was beautiful.

She bites down now on gold piping. Her screams cascade into low sobs. She gazes at him through twists of steam. Her eyes are bright blue, trimmed with red. “Ohhh Elu,” she moans, “I make too much noise.”

He squats for the spoon, his knees cracking like dried wood. “Maybe a little piece of bread,” he says, but when he stands to face her again, she is gone, her eyes rolled back, drowning in blankets. He carries the soup into the kitchen.

The baby slept most of the way to Lubynsti, breathing in shivering breaths the damp wind, the sweet spice of the soil. The moon hung full and bright on the child’s face, on the wet leaves of the forest floor, and on the solitary Jew, walking with his newborn son in his arms. She had wept when she told him to take the baby to the old estate, to give him to a Polish woman who might raise him as her own.

Now the chank chank of snapping branches startled him, and he sat on a downed oak to listen. Three German soldiers appeared on the far bank of the creek, tall and silvery as wraiths. Their voices cut like axes through the slanted woods. “They are like mice, tucked into their little holes,” one said. All three were carrying Lugers, and the tallest had a shoulder-slung carbine. They moved at a stuttering clip, as if tracking a wounded animal. When one of them tried to descend to the water, he came crashing into a dead tree and woke the child with his curses.

The boy’s eyes were peaceful, blue as twilight. They seemed, to the father, unnaturally wise. He tried to chase away the old proverb of wise children and short years, then some new urgency shone in those eyes, and the tiny fingers began to work and gouge at the cheeks. Soundlessly, the father rolled up the blanket and pushed it hard over the beautiful face and held it there for a long time, muffling the baby’s peals. Wet moss soaked up through the seat of his pants.

It was a long time before the Germans passed on to the north, and still longer before the father rose, sore and stiff-jointed. When he arrived at the farmhouse, the sun had already freed itself of the trees. The bundle in his arms lay motionless as a sack of grain. The air smelled of chopped pine, of baking bread. The Polish woman stood shivering at the door, clutching her necklace. Behind her, a man sat eating eggs and onions at a wooden table, refusing to look him in the eyes.

“He is Ben Zion,” the father said, projecting his voice so the man at the table would hear. “But you will give him a Polish name.”

It was a miracle that he had not choked the boy out in the woods, and again a miracle when the Polish woman agreed to take him into her home— this Ben Zion to be named again. In the cool hush of the forest, the father paused to gaze up through the fringed arbor, then he turned around, returned to the house, and stood beneath the window, listening. But he heard nothing.

She is not screaming anymore, only sitting with her back against the carved wooden headboard, the covers pulled up to her waist. Her eyes are watchful; sweat films her upper lip. In her left hand she dandles a diamond bracelet—bright and supple, a masterfully crafted strand of art-deco finery. She smiles, or tries to smile, when he comes into the bedroom. Her white shadow. Tilting the bracelet to the sunlight, she shimmers it like snakeskin. “Do you remember where this is from?”

“From Paris,” he answers. “Sabka, take a piece of toast.”

“Not from Paris, aiver butel, your mind is gone!” She clucks her tongue with such force and petulance that for a moment he forgets the train brakes, forgets the torment of the night before. “From Vlasek’s, in Warsaw!” she cries. “I told you many times. My mother brought me there in the summertime! Vlasek’s . . . oy, such dresses they had in the windows, so luksus, and the hats with the white feathers!” With an upward flinging of hand to hair, a reflex action performed tens of thousands of times, she sets off the hollow cannonade inside her stomach and doubles over in agony.

The phone is ringing, but he cannot hear it over her screams.

High-cheekboned, deliciously thick, with sapphire eyes upturned like a cat’s, Sabka was a once-in-a-village beauty. Even on the march to the arbeitslager she stood out like a princess among commoners in her high heels, black Persian coat, and golden earrings. Her elegance made it all the stranger, all the more dream-like, when the German soldier cuffed her on the head with his bayonet and barked at her, “Dirty Jew, your gold!” Blood dripping from her temple, Sabka slipped the earrings off and handed them over with such dignity and grace that the soldier blushed like a child.

Later, when the column had stopped, the young soldier came back dragging the town watchmaker, Nachmann, by the wrist. Nachmann’s daughter, a girl of eight, scurried along behind them. A cold rain was falling, and Sabka’s coat was matted and lustrous. The soldier stopped before her and fingered her shimmering fur and looked her hard in the eyes. “This pig tried to hide a gold ring from me.” He smiled then, this leather-bound Wehrmacht youth with his bright boots, as if to prove he no longer felt ashamed, could no longer feel ashamed, and he put the pistol in the watchmaker’s ear. His smile twisted into something else the moment before his face caught fire.

The body of Nachmann lay for hours at her feet. His face was white, semi-translucent, like a wax mold of the watchmaker’s face. The daughter kept howling and staring at the wax mask and clawing at her scalp. Sabka tried to calm her, but the next day at the camp the girl became quiet and would not eat, and the Germans took her into a field and sent her along with her father.

Diamonds, like sunlight enchained on the ocean . . . the long manicured fingers of the saleswoman clasping the bracelet over the girl’s wrist. Outside, through the great glass windows, the women of Warsaw are glowing.

In the work camp you waited in line for a crust of bread and watery soup skimmed from cattle feed. You peeled potatoes until your hands bled. You shoveled manure. You slept in the stable, like a pig. When the lights went out, swarms of black flies fed on you, and if you did not clean the stings with saliva the sores became black and infected. Some went barefoot. Some starved. If you could not work you were shot, or taken into the field and chopped to pieces and stacked like so much cordwood. At four o’clock each morning, you lined up outside, and when they called your name you had to say yes.

Each night the Germans took some Jewish women into a room and raped them. The Jewish men sat on the other side of a thin wall and were made to listen. Twice they took Sabka in. Her mother had sewn a secret pocket into her stocking girdle, in which she had stashed the diamond bracelet from Vlasek’s. When she went into the room, Sabka folded the girdle in a corner, tucked it under her rags, and turned slowly to face them. Grappling with a suddenly uncoiling universe, she rose and collapsed, rose, collapsed, like Anna Pavlova’s dying swan, some bewitched contortion of horror and grace . . . Sabka, whose mother had fed her plums in bed, whose nanny had massaged her feet and told her stories of faerie queens until she slept . . . they hurt her, certainly, they devastated her, but they could not go deep enough to destroy her, nor did they find what she was hiding.

She sleeps now, and in sleep her face becomes smooth and quiet as milk. He slides two fingers between the window slats and peers outside. Far below: a blue and bending sea, encrusted in white. Cracking, ever cracking, he lowers himself into the bedside chair and studies her, this woman he never deserved. His body might be gone, he would admit that freely enough. But not his mind. No, a liar must keep a good memory, and his he has nurtured like a fine blade.

He remembers the smell of the chemical tanks, the sheen of the tanning oils in standing vats on the earthen floor of the basement. Remembers her father stripping the animal hide, his arm scraping violently, eyes aflame, shouting from behind his rusty beard, “Go back to your shtetl! You are not for her!”

Sabka, who rode on horse and carriage, who smelled of sweet butter and cheese and rose syrup . . . he could not resist her, though she was only fourteen. And when her father went away to Lublin to treat his arthritis at the hot baths, he came to her every day . . . thus Ben Zion was conceived. And a month later they were arranged to be married.

He hears the phone, but cannot move to answer it. He sits like stone, watching her sleep. Watching her dream.

The train came on a Sunday night: black, cylindrical, pluming evil smoke from the funnel. A triangle of amber lights like demonic eyes. Rumbling, hissing steam from its wheels, towing behind it fifty or so wooden cattle cars. The pale, emaciated Jews, weak from months in the work camp, were herded like sheep across the station floor. Elu pushed toward the back, pounced up onto the ticket counter and stood in peril of his life, scanning the crowd. Upon seeing her he jumped down, forced his way through the waves of prisoners, snatched her by the arm, and tugged against the tide.

“Where are we going?” she said. “This is the wrong way.”

“The train is nearly full,” he said. “If we are lucky, they will have to keep us until the next one.” Toward the back, the soldiers were beating and kicking at the laggards, and husband and wife were turned once again toward the wagons. He drew her close, clamping back his tears. The sight of her gaunt cheeks, the bruised skin beneath her eyes, her thatched hair and black fingernails, sent his throat into convulsions. Every so often, the crack of a shotgun would still the crowd and create a moment of terrifying silence. Then a high German voice would shout, “Macht schnell!” and the shoving would recommence.

They were still on the station floor when the wagons had loaded. Those nearest the tracks began to shuffle away to allow the doors to shut, but the soldiers clubbed them onward and forced them to climb up on top of the others. A frightening sound, like the howling of dogs, caterwauled inside the cars. One woman escaped from the train, gasping and screaming. Her face looked familiar to Elu, a face from his recent past . . . but it could not have been . . . no, the eyes were too black, too bulbous. The woman fell, struck her head on a bench. A soldier came up and shot her through the brain.

As they mounted, men in masks and white uniforms passed along the cars with heavy white sacks, dipping their gloved hands in and tossing quicklime over the passengers. He tried to shield her from the powder, but it rained down on them both, burning like fire on the arms and in their throats. The doors were shut and barred. He held her tightly, coughing, his eyes stinging, unable to breathe.

He remembers. Walking over dead bodies. No, not dead, they were hot . . . breathing . . . old people, children. One boy’s face he remembers. Beaten so badly he had only a nose. No eyes in his face. And some were dead. He remembers. The feeling of teeth and tongues on his legs. Sabka retching, vomiting. Only the thinnest flume of air whistling through the window. Dragging her like dead weight over the slimed limbs. Coughing, everyone coughing. He remembers. His hand rising like a detached thing from the pool of the damned, grabbing hold of the wires in the window. Remembers the scarlet blood, his own blood, coating the metal, and wrenching until he was sure bones or wire must give. And the wires popping loose from the wood. His life . . . an unbroken string of such glittering miracles.

Gathering all his strength, he hefted her full weight above his head and forced her out the window. The cold air roused her and she gave a cry, twirled to grab hold of the sill, and stood with one foot balanced on a small ledger board. “Jump forward!” he shouted. “With the train, jump forward!” The cattle car swayed wildly. Her foot slipped and she dropped, did not jump forward, simply dropped away.

He pulled himself up and launched into the wind and flew and flew and came slamming to the speeding earth and rolled head over legs and popped to his feet and rolled again. Then he was running with the tracks. The train roaring away, the poo-poo-poo-poo-poo of gunfire following him from the last car, bullets slicing at air and earth and trees. He slid on his heels down the bank and dove to the ground, and he lay there until the train was gone. When he stood to his feet, he saw that his hand was badly damaged, perhaps lost. Coughing, he hobbled along the tracks. A pale moonglow like frosting upon the forest.

When he found her she was lying face down on the gravel slope. “Sabka! Sabka!” His voice crackled like burning hay. He turned her over, and with a plunging of the stomach he saw that her face had been shot through . . . open, black, mutilated. But it was not her . . . no, not his Sabka . . . he dropped the body and ran, for minutes or hours he does not remember. He ran, and when he found his wife she was limping at the bottom of the swale, half naked, her ankle swollen, her arms scraped and bloody. But alive. He seized her, looked her in the eyes, and for a moment they did not know each other. Then they went together into the forest.

He picks up the telephone, angles it to his hearing aid. “Let him up,” he says.

Rising now, trying not to wake her with his snares and crackles, he leaves the bedroom, shuffles in socks over Italian marble floors, past silk palms and antique Chinese urns and impressionist oils of windblown poplars. Sunlight filters through the glass dome of the elevator foyer, and he stands under the golden air like some marble museum piece, watching the arrow trace its slow arc up the seventeen floors. It is the waiting that kills you, he thinks. Only the waiting.

The doctor has come alone. Bearded, grizzled, bespectacled, tufts of black hair overflowing the neck of his polo shirt.

“How is she?”

“She doesn’t eat.”

“Did you take her temperature?”

“No. She is cold.”

“How do you know she’s cold if you haven’t taken her temperature?”

“I can feel her, can’t I?”

The doctor frowns. “Where is the girl?”

“She was no good, the girl. She let her go.”

“What?” The doctor straightens up, alarmed. “Why would you do that?”

“Not me!” The old man points toward the bedroom, where the whine of train brakes keens up, as if on cue. “She thought she was stealing. It doesn’t matter. Come, come.”

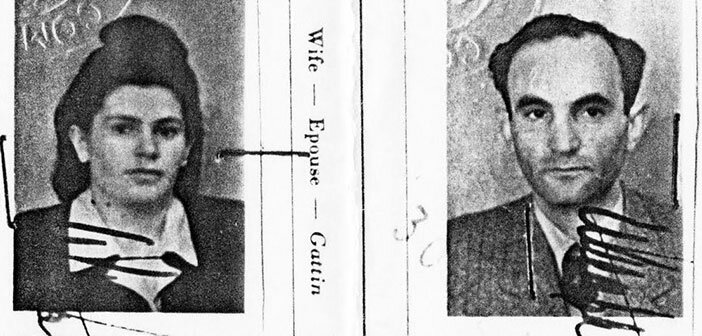

In the corridor, the doctor’s eyes catch and hold on a black-and-white photograph of a younger Elu: tanned, muscular, in a bathing suit and fedora, standing under a wind-brushed coconut palm, one arm draped around a pudgy boy in striped socks and black-framed glasses. “You should have told me you let the girl go,” the doctor says. His voice is quivering.

They tramped through the forest, poison-sick, bleeding, until Elu’s legs gave way atop a pine ridge and he could not stand again. She sat on the ground beside him and wrapped his hand with her scarf. It was not yet dawn. Down below, the light of a cottage glimmered through the trees.

“We can’t go there,” he rasped. “They will turn us in.”

“What do they want with trouble in the night?” she said. “We will ask for something to clean your hand. A bit of food. Then we will leave.”

She lifted him to his feet and supported him down into the hollow. They knocked on the cottage door and a peasant woman—a Ukrainian with red, inflamed eyes—opened it. Behind her, on a dusty bed, lay a skeletal old man, either dead or dying.

“No, no,” the peasant woman said. “I don’t know who I was expecting . . . someone else . . . ” She tried to shut the door, but Sabka thrust her leg forward and blocked it.

“Please, we only need a few things.”

“Fah!” the woman cried. “You jumped from the train to Belzec! They will be looking for you. Go! Go, leave me in peace.”

“Wait!” Sabka held her shin firm against the denting pressure of the wood. “My husband is a doctor, a very well-known doctor, please, let him look at the old man.”

The peasant woman released the door. She had the nose of a drinker, rosy and pustulous. Her hands were covered with soot. She looked at Elu, and her mouth hung open and she began to sob.

“I don’t have my tools,” Elu said, limping inside, “but I will do my best.” He went to the bed and put his ear to the chest and listened to the slow, dull thumping of the old man. He knew nothing about medicine, but he nodded his head knowingly as he inspected a bottle of violet liquid on the bedside table, swirled it to the lamplight. “Good,” he said.

He remembers this. Saying “Good,” and meeting Sabka’s eyes.

Perhaps it was the most astonishing miracle of all when the old man suddenly opened his eyes and folded himself up to a sitting position. As if Elu’s word or the placing of hand to heart had blown wind over his dying coals. The old man’s eyes were so deeply engraved in his skull that when he stood to his feet, Elu had to glance again at the impression on the bed to be sure it was the old man rising and not his ghost. A miracle, no doubt. A resurrection . . . the old man skittering about the room, parsing out clothing and food to the strangers while the peasant wife, half-unbelieving, washed Elu’s hand and dressed it with bandages.

When the sun came up on the next day the old man took them far into the woods, to a deep hole he had dug, and he gave them a board to cover it with and told them to stay there, that he would bring them food. The hole was only big enough for one person to sleep in at a time, and so they would have to take turns. The next day it rained, and water sluiced down the walls and filled their burrow with mud.

A week passed, and they assumed the old man had died. It was spring, and Elu knew how to forage for the good mushrooms. When it was dry enough he built a small fire to fry them on. Rats walked over their faces in the night and they had an old can to hit them with. So they survived the spring and early summer of 1943.

The doctor lays his hand on her forehead. Her body flexes, stiffens, then melts back into the mattress. Her screams take on a slower, deeper tone, as if the touch of his palm has relieved some internal pressure. The old man sits, his joints snapping like timpani drums.

“Elu, what is happening?” A strange noise had woken her in the night, and when she climbed out from the hole she found him crawling on hands and knees, dripping with sweat, and grunting like a beast. “Is it you? Is it you?” he kept saying.

She sat him up against a tree and called out his name until he cocked his head like a dog and looked at her. “Elu! You are sick. Your skin is hot as an oven. You must lie down. Try to drink some water. I will go find vinegar compresses.”

“No!” He pointed toward the hole. “To hell with them! To make us wrap those belts while they watch, to kiss the tzitzit . . . no, I won’t go in! I won’t!”

“You don’t have to do any of that. Come, Elu, lie down.”

“I took the bima, didn’t I? I called Josiah! Josiah! And the old men passed around whiskey? Stuffed their beards with leikach! Stones on the Bes Medrish, I won’t go! I cut my payes! I threw it all away!”

“Elu, you are confused. Lie down, drink some water.”

“Yes, yes . . . ” A look of slow recognition came over his face, like a lost rider happening upon some distant, familiar landscape. “You are right, my Sabka. Of course.”

When he was asleep, she put on the peasant skirt the old man had given her and went out into the forest to look for the cottage. She wandered aimlessly for more than an hour until she came finally upon a dirt road. The dawn was like a blue whisper on the horizon, and the forest began to take shape about her. Certain aspects of the road seemed strangely familiar: the clustered oaks on one side, the tall birches leaning in even rows on the other. She rubbed some earth on her face to give her the tanned look of the peasant girls, and she walked for a while before her heart gave a flutter as she realized where she was.

The doctor’s fingers are blunted, thick as a mason’s, and yet as he draws the liquid into the syringe his motions are tender, almost effeminate. He dabs her arm with alcohol. She opens her eyes, blinks at him. The faintest echo of a scream escapes her lips. Her hand, knobbed and arthritic, rises toward the doctor’s face. “My Schaefela,” she says, removing his eyeglasses. The doctor forces a smile, one blue eye lazing toward the center.

As the needle slides into flesh, her leg muscles constrict and a deep- wrinkled, beatific smile overcomes her face. “I am happy now,” she says. “Please, it was like an emptiness before. But it doesn’t matter anymore, Schaefela. You are here.”

Padding in bare feet down her old gravel drive, she wondered if the cows were out to pasture, or if the servants still sat on the haystack to take lunch. The wet leaves, the road, the budding peonies, all this smelled to her of childhood. She thought of Elu, spreading jam on his bread, clicking his heels together, laughing at some joke of the stable boy’s.

Weightlessly, as if inhabiting a dream, she climbed the steps to the front door. Where her mother’s marigolds had once brightened the porch, a gray urn now stood, and a knotted broomstick.

The Polish woman smiled politely at her. Then her lips turned white.

“I need some vinegar,” is all Sabka said. “My husband is sick.”

The woman backed away slowly, her fingers seeking out her necklace, wrapping it tightly around her knuckles. “Stay there, stay there . . . ”

A trembling excitement, a terror, overtook Sabka. “May I see him?” she said. “Just for a moment?”

But the woman was gone. Muffled voices rose and hushed in the hall, and then the husband appeared in his robe, with his flattened nose and small ice- blue eyes . . . a demonic face, Sabka thought. He stood at a distance from her and hissed, “So, you wanted we should all die, too?”

The ground seemed to fissure, to gape beneath her.

“They would have killed us all! You are lucky, Jewess, to be alive. Now take the medicine and go. And don’t come back! There is nothing for you here.”

“What were you thinking?” The doctor is chewing nervously on his beard, punching numbers into his phone. “She wasn’t eating soup. She was shouting all day! What did you do? You let the girl go!”

Floating, floating now through the forest, her feet swollen and tired, the sky an empty blue cavern, she made her way back to Elu and the hole. He was crawling on all fours, chuffing like a pig. “He made me do it!” he cried. “To study the codes, you understand? To follow those hypocrites in their low black hats! No, I won’t go!”

She lay him down and worked the vinegar compresses over his skin, and after many hours his fever broke. Another miracle. It was the end of May, a month before the Russian bombing raids. A fresh wind blew all the next day, and when Elu was strong enough to stand they went down to the stream and she undressed him and washed him and took him in.

The doctor thrusts open the blinds, tries to crank open the window, but the lever is jammed. He strikes the glass with an open palm and cries out, “I told you to call about this window!” Again he punches the window, this time with a closed fist, but the pane does not budge. The sunlight reveals white streaks in the doctor’s beard. He rears back for a third strike but checks himself, envisioning broken glass. Instead, he swivels around to curse his father, the old fool, for not having the window repaired. But what the doctor sees renders him mute.

Elu is standing over the bed, palms held downward, fingertips fluttering, as if conjuring some fire from Sabka’s chest. What ancient ritual is this . . . this drawing upward of invisible matter from the sleeping woman, this wringing together of hands, as if washing, washing . . . then tossing them skyward?

In the autumn of that year he found work brushing and haltering horses for the Russian soldiers in Lwów. She rolled a cart in town, going from door to door to collect potato skins for the cows. They lived like peasants, worse than peasants, but they saved every zloty and soon they had enough money to travel to Crakow, where Elu came in touch with a cousin who dealt gold on the black market. Poor? Yes they were poor, they had nothing, but did he ask her to pawn the bracelet from Vlasek’s? Not once, though it would have helped very much. He was her servant. He had tilled her father’s soil, had felled trees at the old estate, and though she begged him to sell the bracelet, he would not think of it. It took most of a year to save enough to pay their passage across the sea.

Joy does not keep you alive, nor do you die purely from sorrow. You are created in the moment, made to worship the moment, and so you work and raise this boy conceived in the Holobotow forest, this miracle who will grow in time to be a doctor, you raise him and you feed his mouth in a cold basement of Edward Charles in Montreal. You walk on aching feet to St. Laurent to push your carriage, to buy cheap fish and meat, and it is a great distance every day. You work and save and you bargain and fight to gain purchase on life, and your fortune does not come quickly, but only at the end of a very long walk. The miracles persist, and if they lose their sheen it does not mean they are not miracles all the same.

Her body is not like wax, but of finer stuff. Of porcelain. The paramedics hoist her up onto the gurney and something magical happens: her hand unfolds, and thousands of tiny diamonds waterfall through her fingers, pour into the creases of the bedsheets, shower to the floor like shattered crystal.

His heart convulses as he watches the glittering stones spread and dance over the tiles. Sparkling memories. He remembers. Certainly, he remembers. The women of summertime, in their white feathered crowns. And the windows of Warsaw, all turned to gold.

“All Your Firstborn” originally appeared in The Florida Review, where it won the 2014 Editors’ Award for Fiction, and has been reprinted here with permission of the author.